The Occupation of Alcatraz by Native Americans (1969-1971): A Turning Point in Indigenous Activism

- dthholland

- Dec 13, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 27, 2024

The occupation of Alcatraz Island by Native American activists from 1969 to 1971 marked a significant turning point in the modern Indigenous rights movement in the United States. What began as a symbolic act of defiance against centuries of broken treaties and cultural erasure developed into a prolonged and powerful protest that captured national attention and had a lasting impact on federal policy towards Native Americans. The occupation was the culmination of years of grievances and frustration over the U.S. government’s treatment of Indigenous peoples, and it ignited a wave of activism that reverberated across the country.

The Early Symbolism: 1964’s Brief Occupation

The seeds of the Alcatraz occupation were planted on 8 March 1964, when a small group of Sioux made landfall on the island, which had been abandoned as a federal prison the previous year. Invoking the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which promised that any surplus federal property would be returned to Native ownership, the activists sought to reclaim Alcatraz as Indigenous land. Though their occupation was brief — lasting only a few hours before federal marshals removed them — it was a symbolic act that resonated with Native Americans across the country. This event was a precursor to the larger movement that would follow, highlighting the growing discontent over federal policies of relocation and termination, which sought to encourage Native Americans to leave reservations for urban areas and to strip tribes of their sovereignty.

The Lead-Up to the 1969 Occupation

Throughout the 1960s, the plight of Native Americans was becoming more widely recognised, particularly as a result of the federal government’s relocation and termination policies. Native peoples were being encouraged to move to cities, where they faced poverty, discrimination, and alienation from their cultural heritage. Meanwhile, tribal sovereignty and recognition were being undermined by government actions. This discontent fostered a growing sense of unity and activism among Indigenous communities across the United States, particularly in urban areas like San Francisco, where various tribes had relocated.

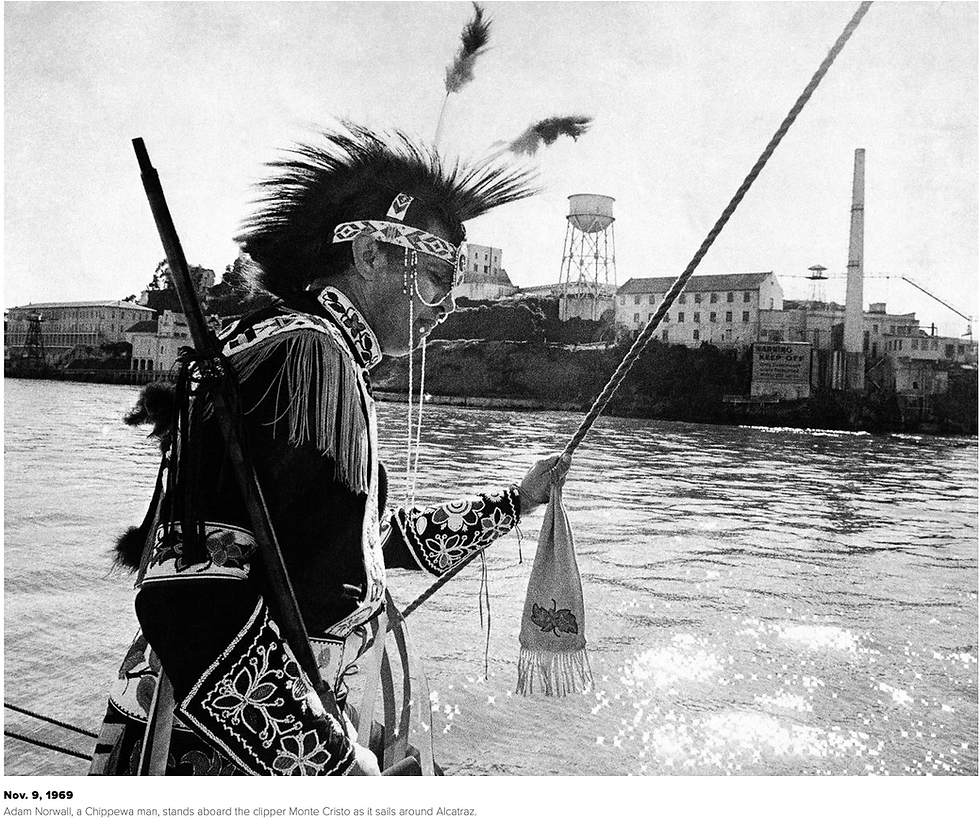

In San Francisco, proposals were being floated about what to do with the disused Alcatraz Island. Local Native American groups began to see the island as an opportunity — a chance to reclaim a piece of land and transform it into a cultural centre for Indigenous peoples. The idea gained traction, and on 9 November 1969, dozens of Native Americans from numerous tribes gathered at Pier 39 in San Francisco and issued a proclamation, claiming Alcatraz by right of discovery. In a symbolic gesture mirroring the offer made by European colonists to Native peoples, they offered to buy the island for $24 in beads and cloth.

A symbolic sailboat cruise around the island followed, during which several passengers leapt overboard and attempted to swim to the island.

While only one succeeded in reaching the shore, the others were swept away by the tide and had to be rescued. That night, 14 determined activists persuaded local fishermen to take them to the island, where they spent the night. These actions were trial runs for the true occupation, which began later that month.

The Full-Scale Occupation Begins: November 1969

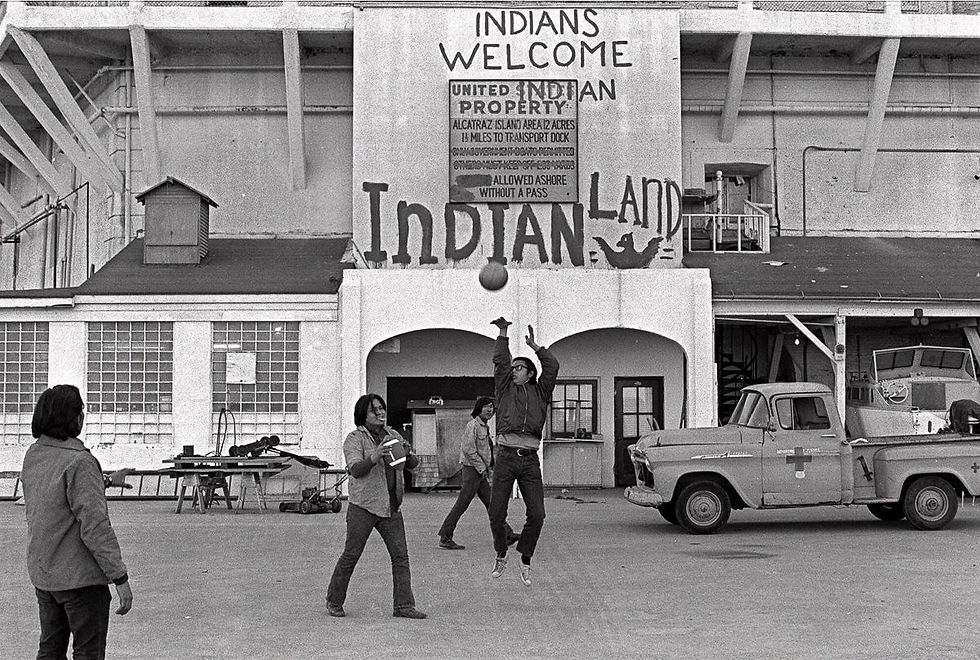

In the early hours of 20 November 1969, nearly 80 Native Americans landed on Alcatraz Island, beginning what would become an iconic and transformative 19-month occupation. The occupiers represented over 20 tribes from across North America and called themselves the “Indians of All Tribes,” symbolising their solidarity in the face of shared grievances. Among the prominent leaders was Richard Oakes, a charismatic Mohawk from New York who had gathered support from Native communities around the Bay Area and from Indigenous students at UCLA.

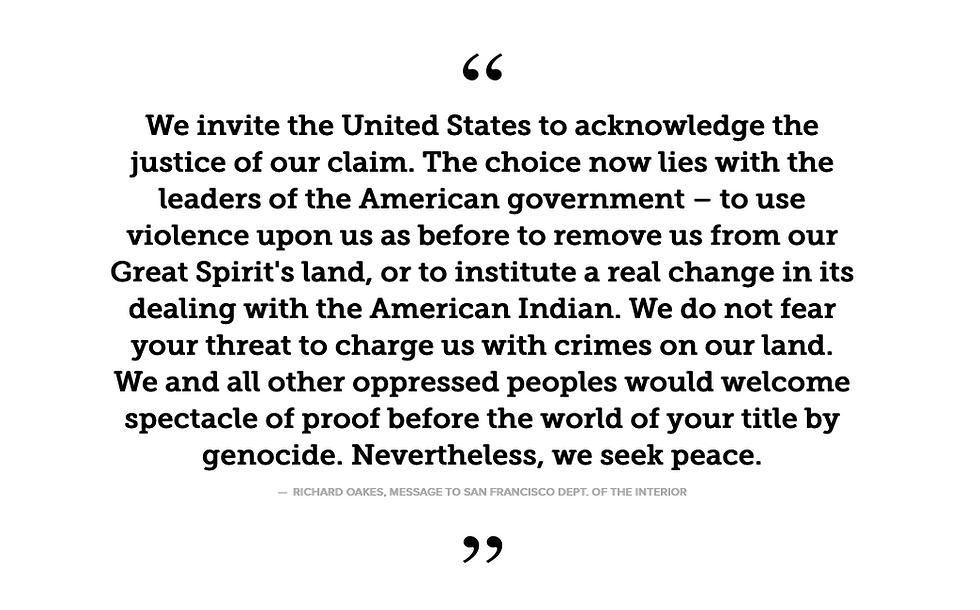

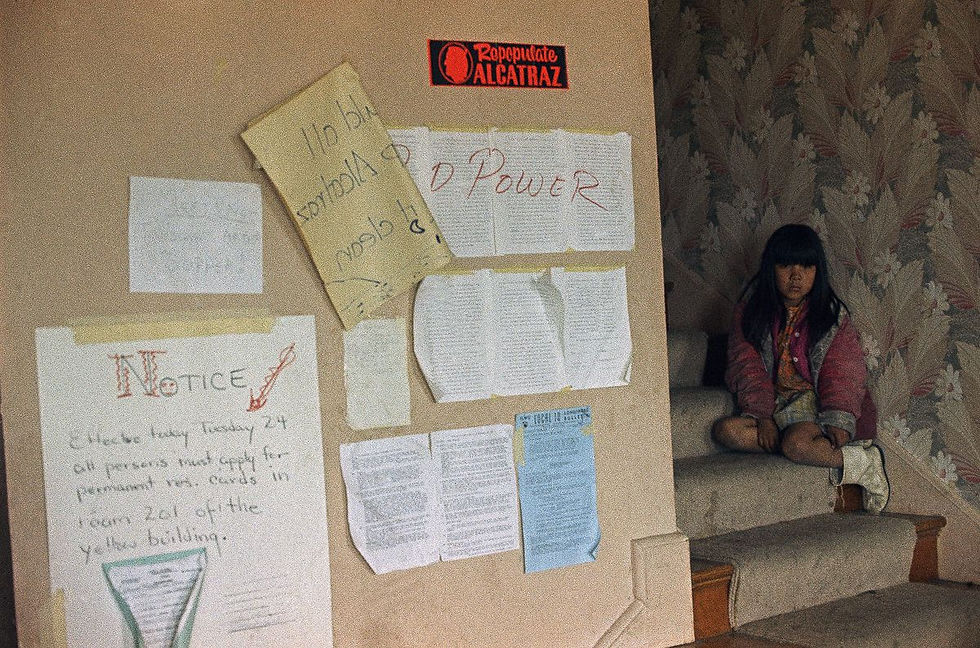

Once on the island, the occupiers quickly set about organising themselves. They established an elected council and began making decisions through consensus. Jobs were assigned to manage the day-to-day operations of the occupation, and the group released a list of demands to the federal government, calling for the return of the island and the creation of a Native American cultural and educational centre. The occupiers invited the government to negotiate, but the initial response was dismissive, with officials demanding that the activists leave.

Government Tactics and Media Attention

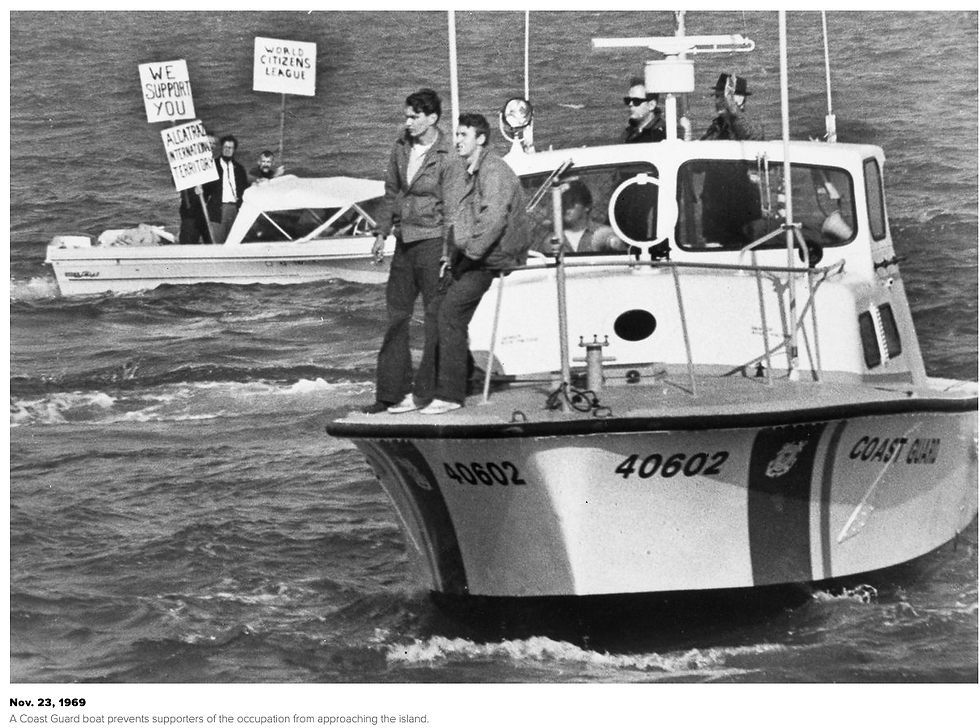

The federal government initially responded by imposing a Coast Guard blockade to prevent supplies from reaching the island, though this tactic was later abandoned in favour of a strategy of non-interference. Officials hoped that by waiting long enough, the occupation would collapse under its own weight. Yet, the opposite occurred: the occupation garnered widespread media attention, shining a spotlight on the long-standing grievances of Native Americans and generating popular support across the country. The media coverage helped to amplify the occupiers’ message of broken treaties, cultural erasure, and governmental neglect.

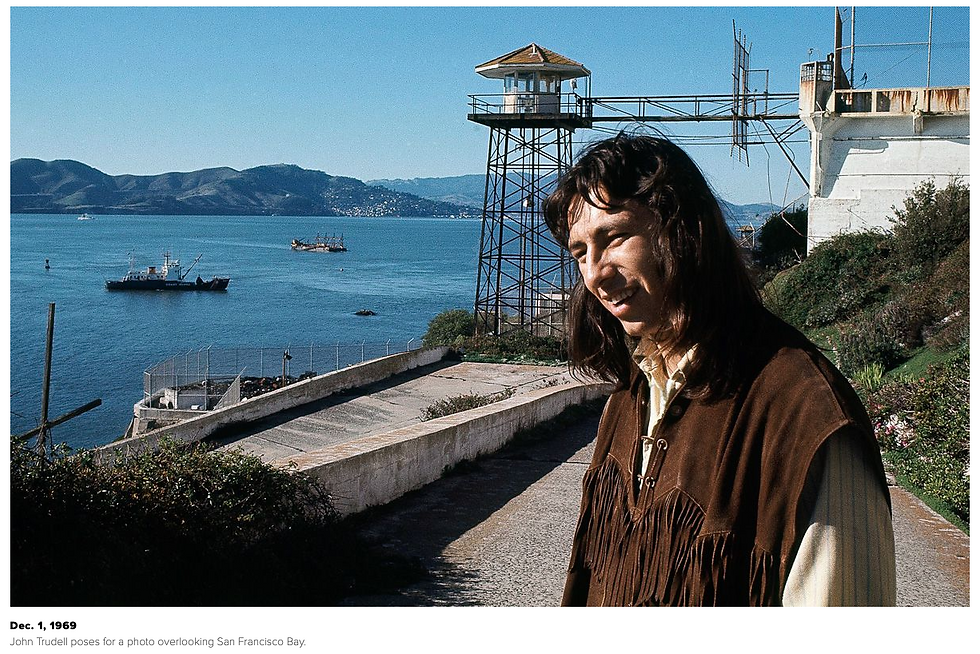

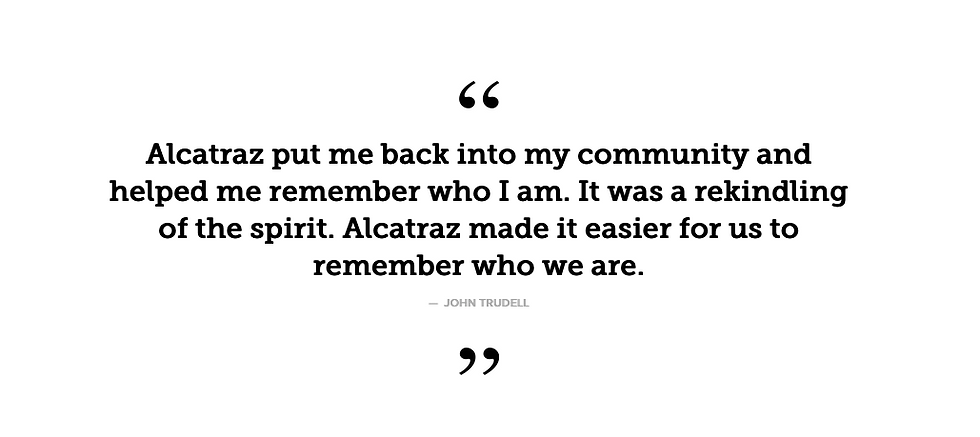

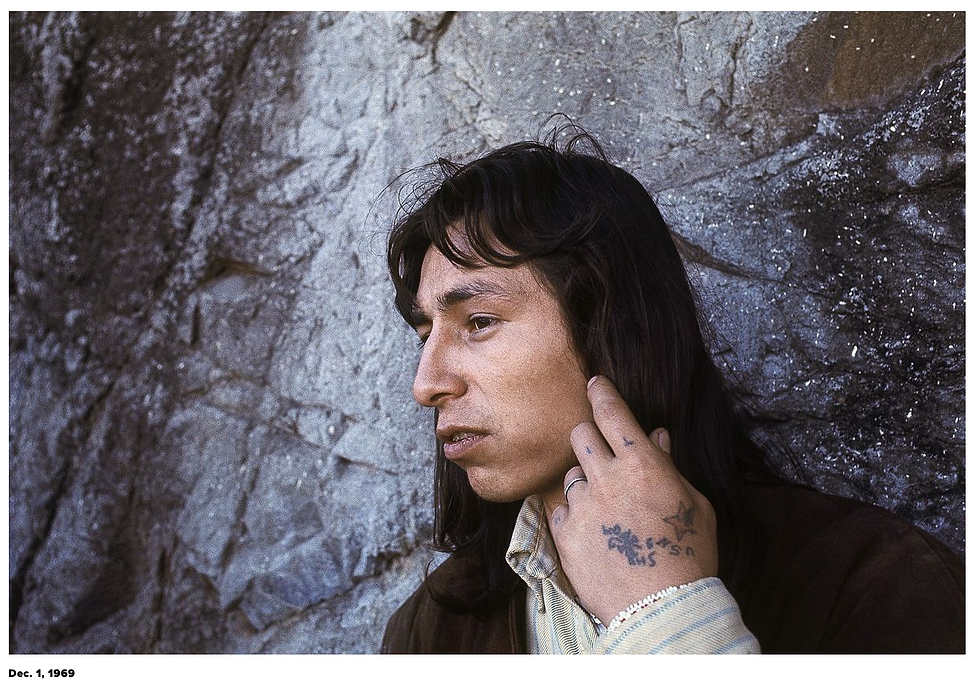

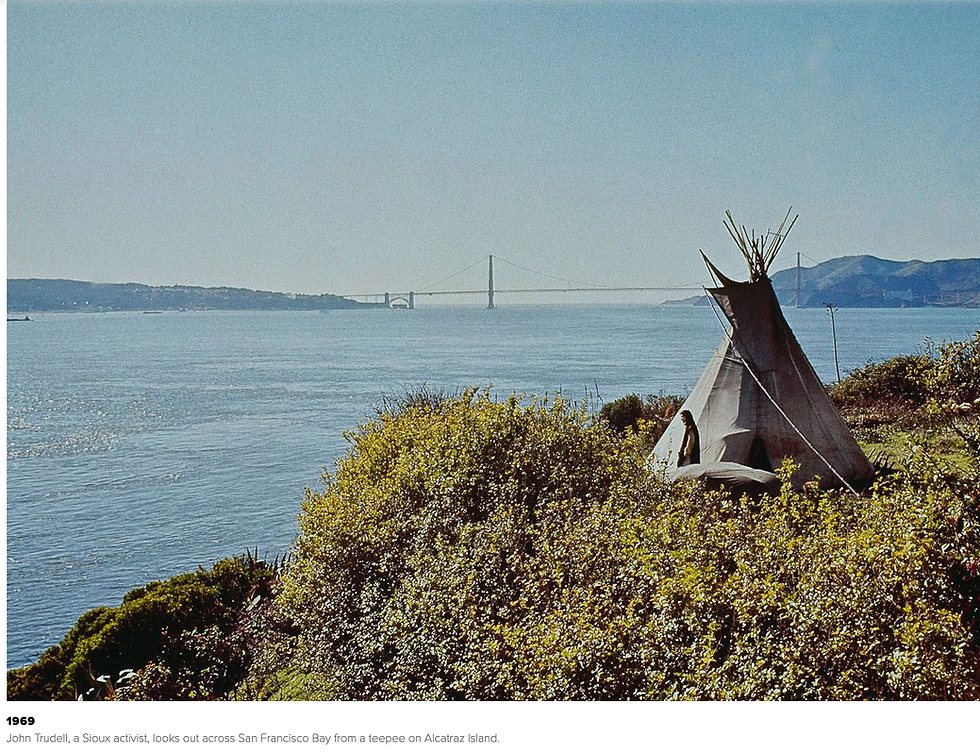

Solidarity protests and occupations sprang up across the United States, as Native Americans and their allies rallied behind the cause. Celebrities like Marlon Brando and Jane Fonda lent their support, and the rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival even donated a boat to assist the occupiers. A pirate radio station, Radio Free Alcatraz, was established by Santee Sioux activist John Trudell, broadcasting the occupiers’ message to a growing audience.

Challenges and Decline of the Occupation

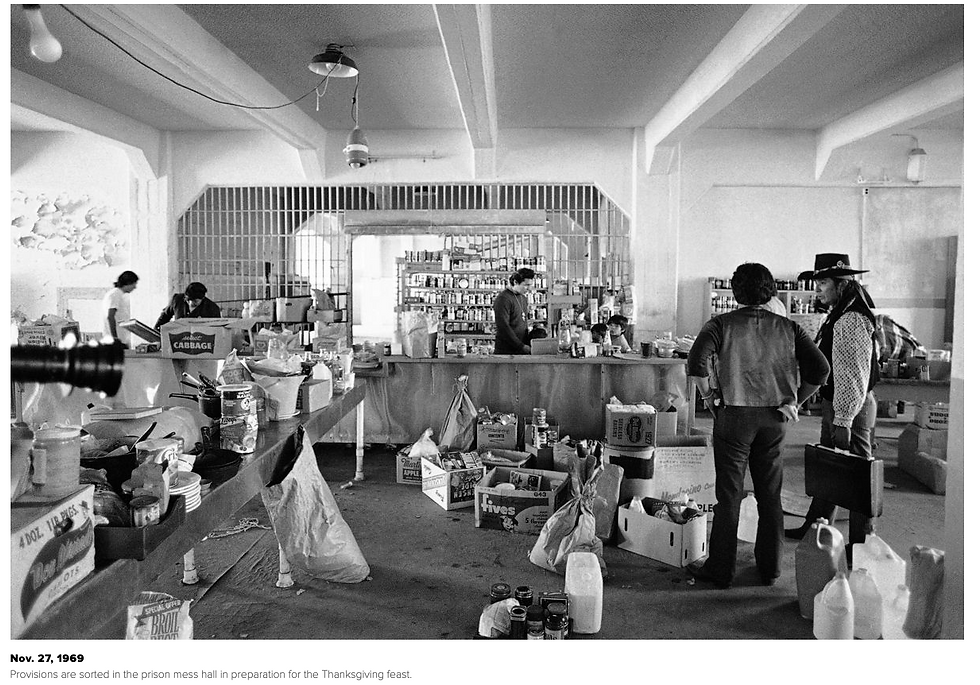

The occupation reached its peak on 27 November 1969, when some 400 Native Americans gathered on the island to celebrate Thanksgiving, marking the event as a day of solidarity and reclamation. However, challenges soon began to emerge. Leadership struggles arose following the departure of Richard Oakes, particularly after the tragic death of his 12-year-old stepdaughter Yvonne in January 1970, which prompted him to leave the island. Factions developed as new occupiers arrived, with some groups more focused on their own agendas than on the original purpose of the occupation. Non-Indigenous individuals, including hippies and drug users, began showing up, complicating the dynamics of the community. Efforts were made to bar non-Natives from staying overnight, but the occupation began to lose its original focus.

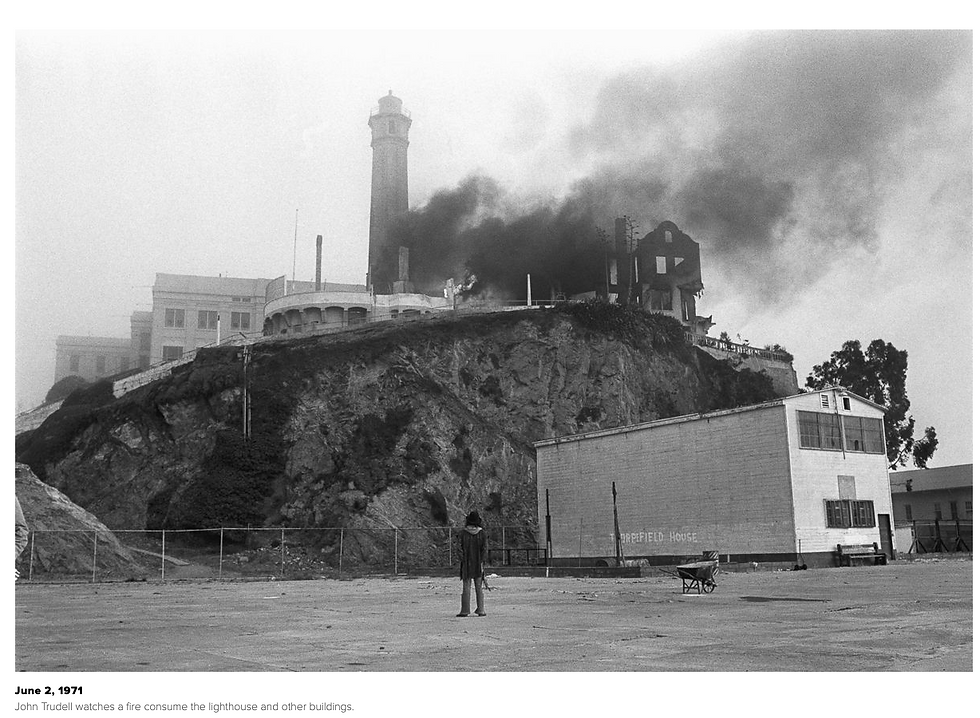

In secret negotiations, the federal government offered an alternative site at Fort Mason in San Francisco for the creation of a Native American cultural centre, but the occupiers rejected the proposal. In response, the government increased pressure on the activists. Electricity, water, and telephone services were cut off, and tensions on the island grew. On 1 June 1971, a fire broke out, destroying several buildings. Both the government and the occupiers blamed each other for the incident, which marked a turning point in the occupation’s decline.

The End of the Occupation and Its Legacy

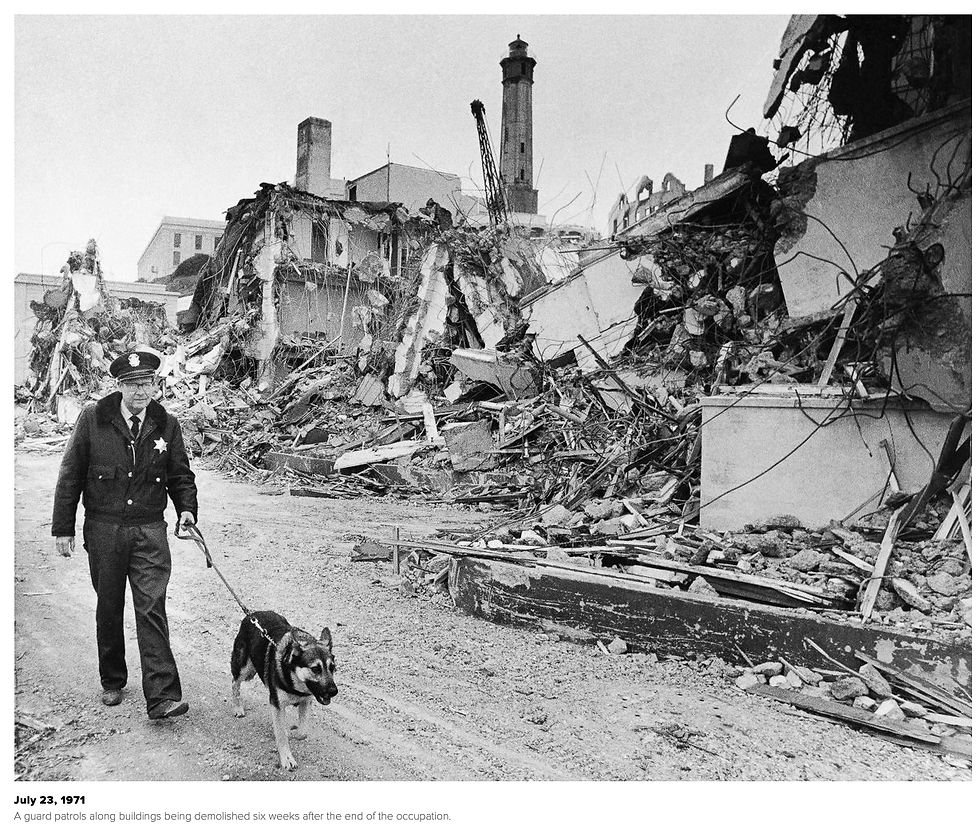

On 11 June 1971, nearly 18 months after the occupation began, federal marshals, with the approval of President Richard Nixon, landed on the island and evicted the remaining 15 occupiers. Though the occupation ended in what appeared to be a defeat, its impact was far-reaching and lasting. The protest had drawn attention to the struggles of Native Americans in a way that few other events had, and it helped to shift public opinion in favour of Indigenous rights.

One of the most significant outcomes of the occupation was the abandonment of the federal government’s policies of relocation and termination. The Nixon administration adopted a new policy of self-determination for Native American tribes, which resulted in a series of reforms that improved conditions for Native peoples. Tribal lands that had been taken were returned, including the sacred Blue Lake area in New Mexico and Mount Adams in Washington State.

The occupation also inspired a new generation of Native American activists, many of whom went on to participate in other landmark protests, such as the 1972 takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters and the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee. The spirit of resistance and solidarity fostered on Alcatraz Island lived on, helping to reshape federal policies and reaffirm the rights of Indigenous peoples.