The Charles M. Schwab House: A Titanic Vision on the "Wrong" Side of the Park

- dthholland

- Jan 23

- 3 min read

Imagine walking along Riverside Drive in the early 20th century and encountering a mansion so grand that it dwarfed even the gilded palaces of Fifth Avenue. This was the Charles M. Schwab House, a 75-room Beaux-Arts chateau that once stood between 73rd and 74th Streets on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Built by steel magnate Charles M. Schwab, the mansion, nicknamed "Riverside," symbolised ambition, audacity, and extravagance—though it ultimately became an object lesson in excess.

An "Elephant" Among Mansions

At a time when New York’s elite clustered on the Upper East Side, Schwab chose to build his dream home on what was then considered the "wrong" side of Central Park. Riverside Drive, though scenic, was not as socially fashionable, and Schwab’s decision raised eyebrows. The mansion’s enormous scale and unconventional location earned it the moniker of a "white elephant"—a possession magnificent yet cumbersome.

Designed by architect Maurice Hébert, the mansion drew inspiration from the finest French Renaissance chateaux. It borrowed elements from Chenonceau, Blois, and Azay-le-Rideau, blending them into a single, cohesive—and colossal—vision. Construction began in 1902 and took four years to complete, costing Schwab $6 million at the time, equivalent to over $200 million today.

Charles M. Schwab House: A Rival to Carnegie’s Mansion

Charles M. Schwab, a self-made man who began as a labourer in a steel mill, had risen to become the president of U.S. Steel and later the founder of Bethlehem Steel Company. His meteoric rise gave him the means to dream big, and Riverside was the ultimate expression of his success. Even Andrew Carnegie, whose own Fifth Avenue mansion was considered the epitome of luxury, remarked, “Have you seen that place of Charlie's? It makes mine look like a shack.”

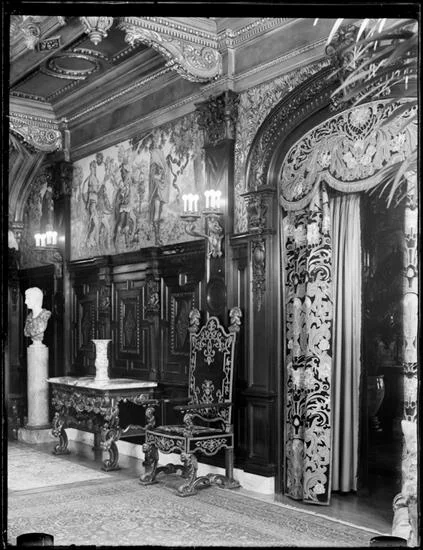

The mansion’s grandeur was unrivalled. Constructed from pink granite and limestone, the four-storey chateau featured a 166-foot tower offering sweeping views of the Hudson River. The interiors were equally opulent: rooms were decorated in styles inspired by French royalty, from a Louis XIV dining room to a Louis XVI parlour. The library, modelled after the Château de Fontainebleau, was a masterpiece of Henri II design.

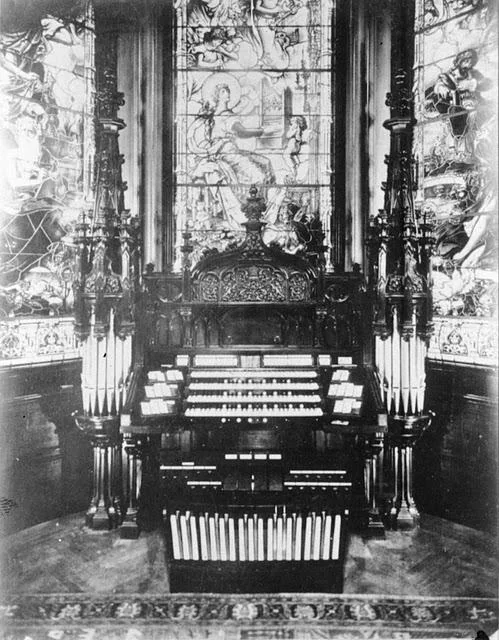

Among the mansion’s extraordinary features were hand-carved mahogany panels, intricately painted ceilings, and a chapel large enough to host an orchestra. The chapel also housed a custom-built pipe organ that Schwab enlarged twice, spending $45,000 on upgrades—equivalent to around $1.5 million today.

A Modern Marvel

No expense was spared to ensure Riverside was a technological marvel. Schwab opened a private quarry in Peekskill, New York, to supply stone for the project, and the mansion boasted a self-contained power plant. It also included one of the first air conditioning systems, an innovation Schwab later boasted about, saying, "When I built it, it was the most modern house in the United States."

The mansion’s basement housed a 20-by-30-foot swimming pool beneath a domed glass roof, a bowling alley, and a 50-foot gymnasium. Six elevators serviced the house, and a tunnel beneath the gardens allowed for discreet delivery of goods. Even the bronze doors—each weighing up to 1.5 tons—were designed to surpass anything found in the grandest Fifth Avenue mansions.

A House of Decline

Despite its splendour, the Schwab House reflected its owner’s restless ambition—and vulnerability. Schwab’s wife, Eurana, reportedly disliked the Upper West Side and withdrew from society after their move. Schwab himself lived a life of extremes, but like many others, he found his fortune to be wiped out by the Great Depression. By 1929, Schwab was bankrupt, and by 1939, he was nearly penniless, living in a modest Park Avenue apartment. He died that same year.

Schwab had offered the mansion to New York City as a mayoral residence, but Mayor Fiorello La Guardia famously refused, asking, "What, me in that?" The house, too grand for any practical use, fell into disrepair. During World War II, its once-manicured lawns became Victory gardens.

The Final Curtain

By 1947, the mansion stood empty, its grandeur faded. Its interior fittings were auctioned off, drawing nostalgic visitors like S. Archer Gibson, Schwab’s former organist, who returned to see the instrument he had once played. The massive organ, too large to remove intact, was slated for destruction but was partially salvaged by Eric Sexton, who reinstalled parts of it in Maine.

The Schwab House was demolished in 1948, and in its place rose a red-brick apartment complex ironically named "The Schwab House." The building, practical and unremarkable, bore no resemblance to the architectural masterpiece it replaced.