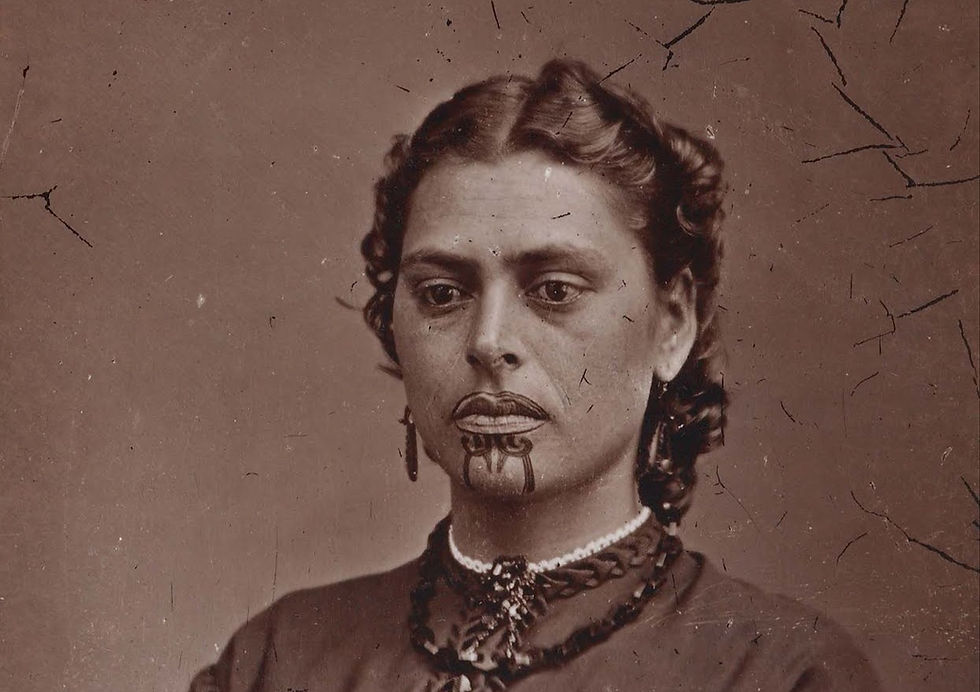

Portraits Of Tā Moko Tattooed Māori Women Before The 1907 Tohunga Suppression Act.

Tā moko, the traditional Māori tattooing practice, is a deeply spiritual and culturally significant art form that has been integral to Māori identity for centuries. This art involves intricate patterns, typically tattooed on the face and body, symbolising lineage, social status, achievements, and the wearer's connection to their ancestors. While Tā moko was practised by both men and women, moko kauae, the chin tattoo, was specifically reserved for Māori women.

For Māori women, moko kauae was more than just a physical marking; it was a visible representation of their mana (spiritual power) and whakapapa (genealogy). It marked the transition from girlhood to womanhood and was a sign of a woman’s strength, authority, and wisdom. Each moko was unique, telling the story of the wearer’s life, heritage, and community.

The process of receiving tā moko was long and painful, often taking up to a year to complete a single piece. The pigment used in tā moko, known as wai ngārahu, was usually made from charcoal mixed with oil or liquid from plants and was stored in special containers. Women were traditionally tattooed on their lips, around the chin, and sometimes the nostrils, with moko kauae being the most common form for women.

The decline of Tā moko, and in particular moko kauae, was a direct result of colonisation and the subsequent efforts to assimilate Māori culture into Western norms. As European settlers arrived in New Zealand during the 18th and 19th centuries, they brought with them their own beliefs, religions, and social structures, which often conflicted with Māori traditions.

Christian missionaries played a significant role in this cultural shift. They viewed the practice of tattooing as pagan and sought to convert Māori people to Christianity. Women with moko kauae were often discouraged from displaying their tattoos and were pressured to abandon the practice in favour of adopting European customs.

The British invasion of New Zealand led to further erosion of Māori cultural practices. The Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907, which outlawed Māori medical practices, had a profound impact. Since these practices were closely linked to Māori spiritual and cultural traditions, the suppression of tohunga (spiritual healers) effectively outlawed a significant part of Māori culture, including Tā moko. This led to a sharp decline in the practice, and Māori culture was increasingly viewed as a relic of the past, with some even describing the Māori people as a “lost race.” The Act was not repealed until 1962, by which time much of the tradition had been lost.

The rapid urbanisation and modernisation of New Zealand in the 20th century further contributed to the decline of traditional Māori practices. As Māori people moved to cities in search of work and better opportunities, they were often separated from their tribal lands, communities, and cultural practices. This disconnection from their roots made it difficult to maintain traditional customs, including Tā moko.

Despite the cultural pressures and legal restrictions, some Māori women continued to receive moko kauae into the early 20th century. Historian Michael King, in the early 1970s, interviewed over 70 elderly women who had been given their moko before the 1907 Tohunga Suppression Act. These women were among the last to bear these traditional markings, having received them during a time when Māori culture was under significant threat.

Some of the last women to bear moko kauae were born in the late 19th century and grew up in rural Māori communities where traditional practices were still upheld. Their moko kauae was often a source of pride and a strong connection to their ancestors, even as they witnessed the world around them changing rapidly.

Despite its near disappearance, moko kauae has experienced a resurgence in recent decades as part of a broader Māori cultural revival. Since the 1990s, there has been a revival of Tā moko for both men and women, as a sign of their cultural Māori identity. This revival is driven by a new generation of Māori women who are reclaiming their heritage and proudly wearing moko kauae as a symbol of their identity, resilience, and connection to their ancestors.

Today, moko kauae is seen as a powerful expression of Māori womanhood and a visible statement of cultural pride. The stories of the last women to wear moko kauae in the early 20th century have become an important part of this revival, inspiring contemporary Māori women to honour and continue the tradition.

Sources

Te Awekotuku, Ngāhuia. "Māori Women and Moko: The Spirals of Power." Cultural Survival Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 4, 2001, pp. 55-57.

Jones, Jessica. "The Resurgence of Tā Moko in Aotearoa: A Symbol of Identity." Journal of Māori and Pacific Development, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 145-161.

Salmond, Anne. Two Worlds: First Meetings Between Māori and Europeans, 1642-1772. University of Hawaii Press, 1991.

King, Michael. The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books, 2003.

Ellison, Te Rina. "Moko Kauae: A Tradition Revived." Te Karaka, vol. 79, 2018, pp. 12-19.

Keenan, Danny. "The Impact of Colonisation on Māori Identity and Culture." New Zealand Journal of History, vol. 49, no. 2, 2015, pp. 52-70.

Jahnke, Huia. "Māori Women and Tattooing: A Contemporary Perspective." Journal of Indigenous Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2020, pp. 84-101.

Pere, Rose. "Urbanisation and the Decline of Māori Traditional Practices." Māori Studies Review, vol. 6, no. 3, 2016, pp. 22-37.