“Kill The Indian In Him And Save The Man” The Forced Cultural Assimilation Of Native Americans.

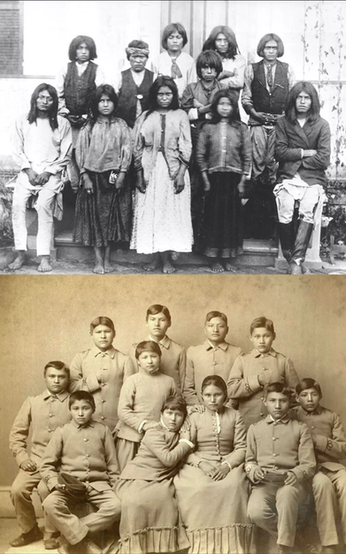

During the late 19th century, the federal government of the United States embarked on a campaign of cultural assimilation aimed at eradicating the identity, traditions, and practices of Native Americans. The government’s approach was not to engage with Native American cultures, but rather to suppress and transform them. Central to this process was the establishment of a network of boarding schools, the most notorious of which was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded in Pennsylvania in 1879. Under the direction of Richard Pratt, a former Army officer, believed that Native American children could only succeed in society by abandoning their heritage and fully adopting Euro-American customs.

His infamous motto, “kill the Indian in him and save the man,” became the guiding principle for the school’s operations. Pratt’s vision was to transform Native children into what he considered "civilised" members of society by erasing every trace of their culture and upbringing.

The Carlisle school served as a national model for the assimilation effort, and more than 400 day and boarding schools were established near Native reservations. These institutions, many of which were operated by religious organisations, were designed to strip Native children of their cultural identities. Between 1880 and 1902, at least 25 off-reservation boarding schools were established to forcibly separate children from their families and communities. It is estimated that around 100,000 Native American children were taken from their homes to attend these schools. Once there, they were forbidden to speak their native languages, forced to abandon traditional religious beliefs, and made to adopt English names in place of their own.

In many cases, the children were leased out to white families as indentured servants, an exploitative practice that added another layer of dehumanisation to their experience. This systematic attempt to destroy Native identity was not just confined to the classroom. Hair, often considered sacred in many Native cultures, was cut short. Traditional clothing was replaced with Euro-American uniforms, and children were taught to feel shame about their heritage.

For Native American families, this cultural assault was devastating. Parents who resisted the forced removal of their children faced severe consequences. Many were imprisoned, while others had their children taken by force. The Hopi leader, Chief Lomahongyoma, and 18 other members of his tribe were arrested and sent to Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay for refusing to send their children to government-run boarding schools. They also resisted the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ efforts to impose farming practices that went against their cultural values and way of life. The imprisonment of Chief Lomahongyoma became symbolic of Native American resistance to assimilation policies, but it also demonstrated the lengths the government was willing to go to enforce its oppressive agenda.

The living conditions at these boarding schools were often deplorable. A report commissioned by the Interior Department in 1928, commonly referred to as the Meriam Report, exposed the inhumane treatment of children at these institutions. The report revealed that the schools were overcrowded, the food was insufficient, medical care was inadequate, and child labour was rampant. Many students were required to perform hard labour to maintain the facilities, often to the detriment of their health and education. The Meriam Report’s findings caused a public outcry, leading to some reforms and the eventual closure of most off-reservation boarding schools by the 1930s.

However, the damage was done. Many Native children who attended these schools lost their connection to their culture, language, and families. The trauma endured by these children did not end when they left the schools. For generations, the effects of this forced assimilation have rippled through Native communities, contributing to a profound sense of cultural dislocation and loss.

Efforts to revitalise Native languages and traditions have been ongoing for decades, but the legacy of the boarding school era remains a painful chapter in American history. The cultural erasure that began in these institutions continues to have lasting impacts on Native American communities. The suppression of Native identity and autonomy by these policies, which stretched over half a century, constitutes one of the darkest and most damaging aspects of U.S. federal policy towards Native Americans.

Resistance and Rebirth

Despite the widespread impact of forced assimilation, Native American communities have worked tirelessly to revive their languages, traditions, and cultural practices. Many survivors of the boarding school era and their descendants have been at the forefront of these efforts, passing on stories, rituals, and languages that were nearly extinguished.

The work of Native activists has helped reclaim much of what was lost. Tribes have re-established traditional practices, revitalised languages that were on the brink of disappearing, and fought for the acknowledgment of their experiences. Tribal-run schools today aim to give Native children an education that embraces their heritage, rather than one that seeks to erase it.

Institutions like the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition continue to work towards healing the wounds left by the boarding school system, advocating for reparations and the proper commemoration of those who were impacted by these policies. These efforts acknowledge the strength and resilience of Native American cultures in the face of systematic attempts to destroy them.