My Good Friend Roosevelt: The Time Young Fidel Castro Wrote to the U.S. President (and Asked for a Tenner)

- dthholland

- Feb 10

- 3 min read

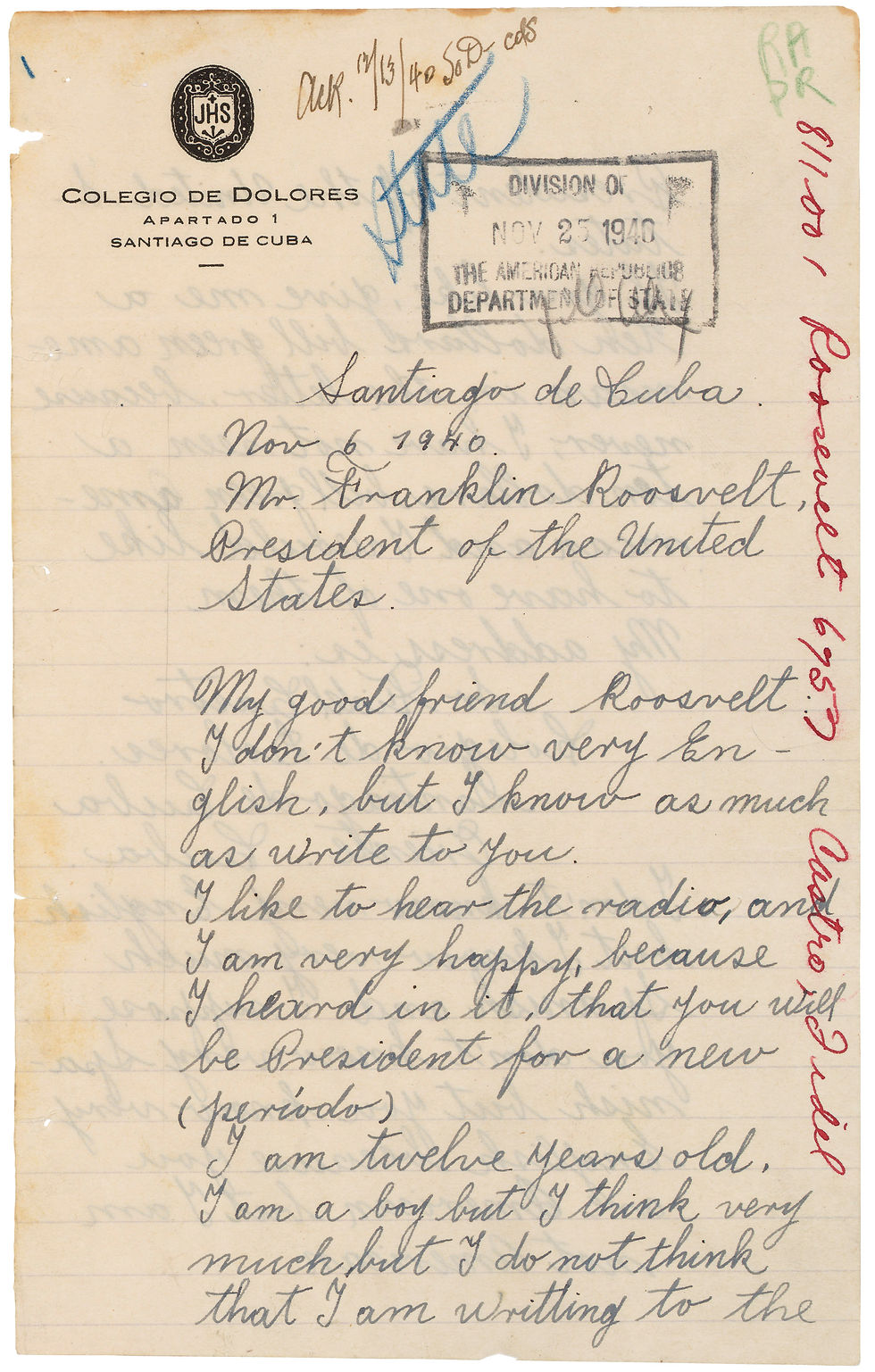

It is an amusing yet historically revealing episode that, in 1940, a young Fidel Castro—yes, that Fidel Castro—decided to write a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. On official Colegio Dolores stationery, in painstaking cursive but charmingly broken English, the 14-year-old Castro (who, for reasons likely tied to school admissions, claimed to be 12) reached out to the leader of the free world with a straightforward and rather audacious request: ‘If you like, give me a ten dollar bill green American.’

Dear Mr. President: About That Ten Dollars...Yours, Castro

One day after FDR’s landslide re-election victory on 6 November 1940, young Fidel, then a student at the prestigious Jesuit-run Colegio Dolores in Santiago, Cuba, sat down to pen what is surely one of the most unexpected pieces of diplomatic correspondence in history. His letter begins grandly: ‘My good friend Roosvelt,’ a level of familiarity that most world leaders would hesitate to use even after years of negotiation. One might even say that, better than anyone, Castro understood from an early age just how entwined Cuba’s fate was with that of the United States.

However, rather than presenting a grand vision for hemispheric relations, he got straight to the point: the request for ten dollars. Not for frivolous spending, mind you—no mention of chocolate, cinema tickets, or baseball gear. No, Castro simply wanted to see what a real American bill looked like. Even at this tender age, he was already expressing the curiosity that would later fuel a life of political ambition. But Roosevelt, in his wisdom—or perhaps just due to some overworked White House intern’s reluctance to deplete the petty cash—did not comply.

Schoolyard Diplomacy and a Missed Investment

If FDR had possessed a crystal ball and foreseen the future leader of Cuba reaching out to him as a schoolboy, might he have sent the ten-dollar bill as a goodwill gesture? Could it have altered the course of U.S.-Cuban relations? Unlikely. But it would have at least kept young Fidel from calling Americans ‘assholes’—as he reportedly did after his polite and expectant request was ignored.

Despite this minor diplomatic snub, Castro did receive a response on official White House stationery, a trophy that he proudly displayed on the school bulletin board. According to historian Luis Aguilar, who attended Colegio Dolores at the time, the letter boosted Castro’s standing among his peers. In a school where the sons of Cuba’s wealthiest families often looked down on him and his brothers due to their illegitimacy and rural origins, this recognition from Washington was a social triumph. One can imagine the scene: an eager Fidel parading the letter around, only for his classmates to skim past Roosevelt’s words in search of any mention of an enclosed ten-dollar bill. Finding none, Castro likely received a fresh round of jeers.

Iron Mines and Political Foreshadowing

Not one to leave matters to chance, Castro had even added a postscript to sweeten the deal: ‘If you want iron to make your sheaps [ships], I will show to you the bigest (minas) of the land. They are in Mayarí, Oriente, Cuba.’ A casual offer, perhaps, but one that reflected an awareness of Cuba’s economic resources—an awareness that would later play a significant role in the island’s Cold War alignment. The American-owned Spanish-American Iron Co. had been extracting iron ore there since the early 1900s, and young Fidel saw an opportunity to pitch a business deal to the most powerful man in the world. That Roosevelt didn’t bite was another missed investment; in time, it would be the Soviet Union that would appreciate the value of Cuba’s strategic resources.

The Ghost of Ten Dollars Past

Nineteen years later, when Castro travelled to Washington as Cuba’s revolutionary leader, he was keenly aware of the precedent set by Latin American politicians who came to the U.S. cap in hand. He told his finance minister, Rufo López-Fresquet, ‘I don’t want this trip to be like that of other Latin American leaders who always come to the U.S. to ask for money.’ Could his early ten-dollar humiliation have influenced his approach to U.S.-Cuba relations? Perhaps not directly, but as any historian will tell you, childhood slights have a way of lingering in unexpected ways.

The irony, of course, is that Castro would go on to be one of the most formidable critics of the United States, railing against its economic policies and imperialist tendencies. One wonders if, in some alternate universe, Roosevelt’s personal secretary had decided to tuck a crisp ten-dollar bill into that envelope and changed the course of history. Would a delighted Fidel have framed it? Saved it? Used it to buy baseball cards? We will never know.

But we do know this: while Castro never got his ten-dollar bill, he certainly got America’s attention in the decades to come. And that, perhaps, is worth far more than ten bucks.