Blood in the Yard: The Attica Prison Uprising and the Fight for Prison Reform

In 1971, the Attica Correctional Facility in New York became the centre of one of the bloodiest and most significant prison uprisings in American history. The Attica prison riots exposed the brutal conditions within the American penal system and ignited a national conversation about prisoners' rights, racial inequality, and state violence. Over the course of five days, the world witnessed a violent confrontation that led to the deaths of 43 people, including prison guards, staff, and inmates, and left a lasting legacy on the American prison system.

Overcrowding and Brutal Conditions

Attica Correctional Facility was meant to hold 1,600 inmates, but by 1971, it housed around 2,200 prisoners. This overcrowding led to rationing of essential supplies, worsening already inhumane conditions. Prisoners were allotted just one roll of toilet paper per month and permitted only one shower per week. They spent 14 to 16 hours a day confined to their cells, with limited access to reading materials, and their mail was heavily censored. Visits from family members were conducted through mesh screens, eliminating any physical contact. Medical care was disgraceful, and racism was rampant throughout the prison.

As one historian later noted,

"Prisoners spent 14 to 16 hours a day in their cells, their mail was read, their reading material restricted, their visits from families conducted through a mesh screen, their medical care disgraceful, their parole system inequitable, racism everywhere."

These conditions created a climate ripe for rebellion, and by September 1971, the prisoners had reached their breaking point.

The Uprising Begins

On the morning of September 9, 1971, tensions finally boiled over. Just after dawn, as inmates were on their way to breakfast, a small group of prisoners overpowered nearby guards and made their way through a shoddy gate into the heart of the prison, known as "Times Square." The number of rioters quickly swelled to over 1,200 as prisoners from across the facility joined the revolt. Armed with homemade weapons, including shivs and clubs, the inmates attacked prison officers, severely injuring several and killing one guard, William Quinn, who would later die from his injuries.

The inmates seized control of multiple cell blocks and burned down the prison chapel, signalling their control over the facility. Meanwhile, state police quickly regained control of most of the prison, but by the time they had done so, 1,281 prisoners had taken 39 guards and prison employees hostage and retreated to an exercise yard known as D Yard.

The Prisoners’ Demands

The prisoners were not acting purely out of anger; they had clear demands for reform. Soon after taking control of D Yard, they began organising themselves, forming a governing body that designated some inmates to act as security, others as medics, and still others as negotiators. They also set about drafting a list of demands, which they titled The Attica Liberation Faction Manifesto of Demands. This document outlined 33 specific requests, ranging from better medical treatment to more religious freedoms. They demanded basic necessities such as daily showers and more than one roll of toilet paper per month, and they called for an end to physical abuse by prison guards.

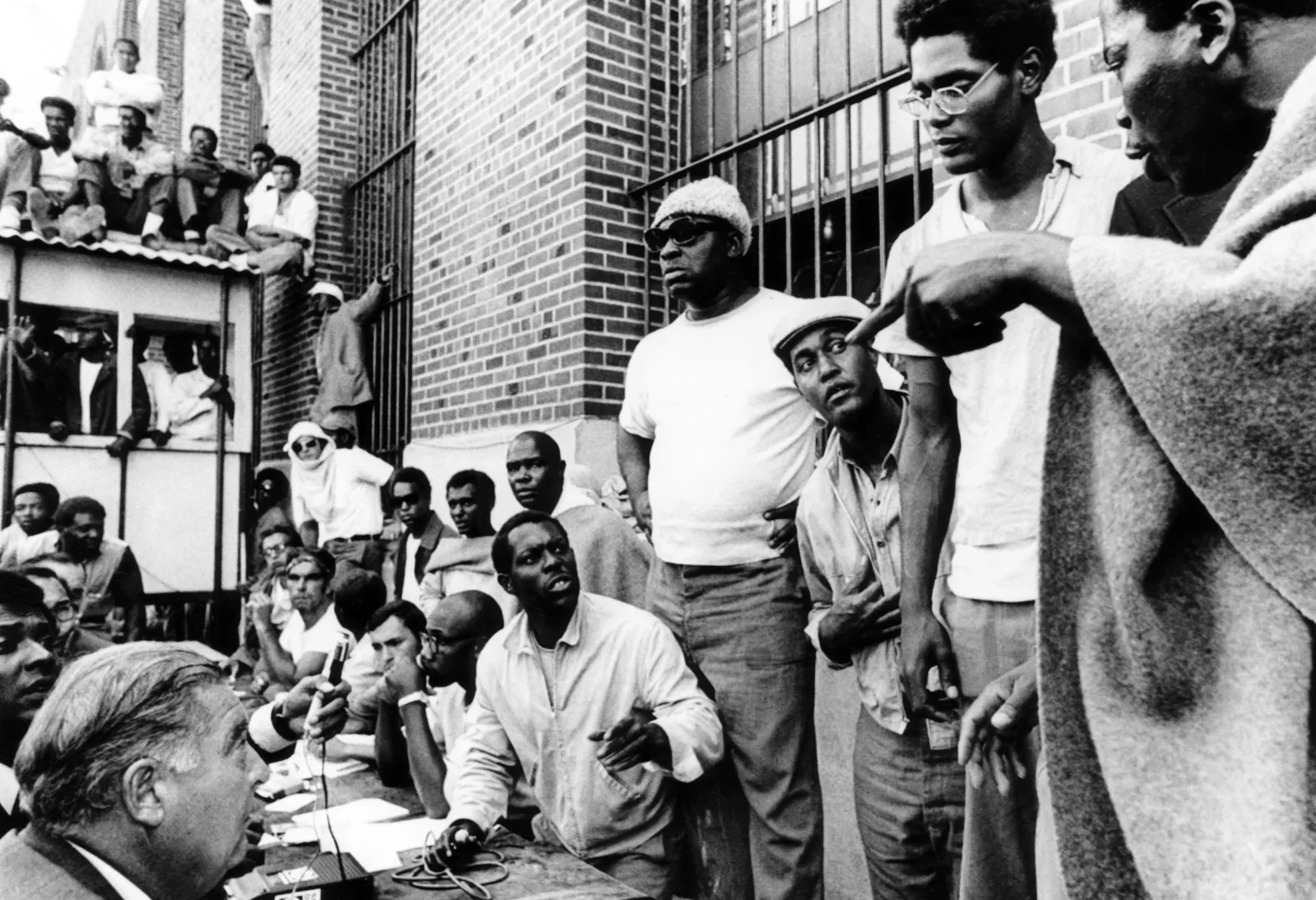

The prisoners also requested amnesty for their actions during the uprising, a point that would prove contentious during negotiations. They called for outside observers to oversee the negotiations and ensure fair treatment. Among those invited were civil rights attorney William Kunstler, New York Times columnist Tom Wicker, Minister Louis Farrakhan, and Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale. While some, like Farrakhan, declined to participate, others, including Seale and Wicker, agreed to meet with the prisoners.

The Stand-off

Negotiations initially seemed promising. New York Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald agreed to 28 of the prisoners’ demands, and talks between the inmates and state officials moved forward. However, the issue of amnesty remained unresolved, and as time passed, the situation grew more tense. By the evening of September 12, both Oswald and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller had decided that the time for negotiation was over. They began preparing to retake the prison by force.

At 8:25 a.m. on the morning of September 13, Oswald delivered a final ultimatum to the prisoners, demanding their full surrender. The response from the inmates was immediate: they placed knives against the throats of the hostages and prepared for battle. Meanwhile, state police and National Guard troops surrounded the prison, helicopters hovered overhead, and hundreds of officers stood ready to storm the yard.

At precisely 9:46 a.m., the helicopters dropped tear gas over D Yard, and within moments, the assault began. State police, correctional officers, sheriff's deputies, and park police officers stormed into the yard, guns blazing. Armed with shotguns loaded with buckshot and unjacketed ammunition in violation of the Geneva Convention, they unleashed a brutal assault on the inmates. Thousands of rounds were fired into the smoke-filled yard, killing 29 inmates and 10 of the hostages and wounding 89 others.

The Aftermath

The attack was over within 20 minutes, but the violence did not end there. Prisoners who had surrendered were subjected to brutal reprisals. They were forced to run a gauntlet of officers wielding nightsticks and ordered to crawl naked over broken glass. Some inmates were shot after they had already surrendered, and others were subjected to further abuse in the days that followed.

In the immediate aftermath of the assault, state officials attempted to cover up the full extent of the carnage. Both Rockefeller and Oswald claimed that the hostages had been killed by the inmates, not by the police. They even spread false rumours that one of the hostages had been castrated by the prisoners. However, autopsies quickly revealed the truth: all 10 hostages had been killed by police gunfire. This revelation sparked outrage and led to a congressional investigation into the events at Attica.

The National Response

The Attica prison uprising did not occur in a vacuum. It was part of a broader wave of activism and protest that was sweeping through American prisons at the time. Across the country, inmates were demanding better living conditions, fairer treatment, and an end to racial discrimination within the penal system. The federal government viewed these protests as a serious threat, and as historian Heather Ann Thompson later uncovered, officials across the federal government were deeply involved in the events at Attica from the very beginning.

On the first day of the uprising, the FBI began sending memos to various branches of the military and intelligence services, including the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, CIA, and the White House. Attorney General John Mitchell was particularly concerned about the influence of leftist activists and civil rights leaders, and J. Edgar Hoover's FBI had long been monitoring and sabotaging civil rights organisations through its COINTELPRO programme.

President Richard Nixon was also deeply involved in the government’s response to the uprising. In taped conversations with aides, Nixon expressed support for Rockefeller’s decision to use force, viewing the Attica uprising as part of a broader “black uprising” that needed to be crushed. “You see it’s the black business...he had to do it,” Nixon remarked to his aides. He believed that the brutal suppression of the uprising would send a message to activists and deter future prison riots.

A Lasting Legacy

The Attica prison uprising was a turning point in the history of American prisons, but its legacy is complex. On the one hand, it brought attention to the appalling conditions inside prisons and led to some reforms, particularly in regard to religious freedoms and medical care. On the other hand, many of the prisoners’ demands were never met, and the “tough on crime” policies of the 1980s and 1990s rolled back many of the gains made in the aftermath of the uprising.

The uprising also had a profound impact on public perceptions of prison reform. Before the events at Attica, there was growing sympathy for prisoners' rights, and many Americans recognised the need for reform. But the violent suppression of the uprising, coupled with the misinformation spread by state officials, led to a hardening of attitudes. Many Americans came to view the inmates not as individuals seeking justice, but as dangerous criminals who needed to be controlled by any means necessary.

Decades later, the legacy of Attica continues to shape the struggle for prisoners’ rights. Inmates across the United States are still fighting for many of the same basic demands made by the Attica prisoners in 1971: better living conditions, fair treatment, and an end to racial discrimination. While some progress has been made, the struggle for justice within the American penal system is far from over.

Sources:

Thompson, Heather Ann. Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Pantheon Books, 2016.

Wicker, Tom. A Time to Die: The Attica Prison Revolt. Haymarket Books, 2011.

United States Congress. Attica Prison Uprising, 1971: A Retrospective on the Events and their Impact on the American Justice System. Congressional Hearings, 1972.

Kommentare