Arnold Rothstein: The Gambler Who Helped Build New York’s Underworld

- dthholland

- Nov 4, 2024

- 6 min read

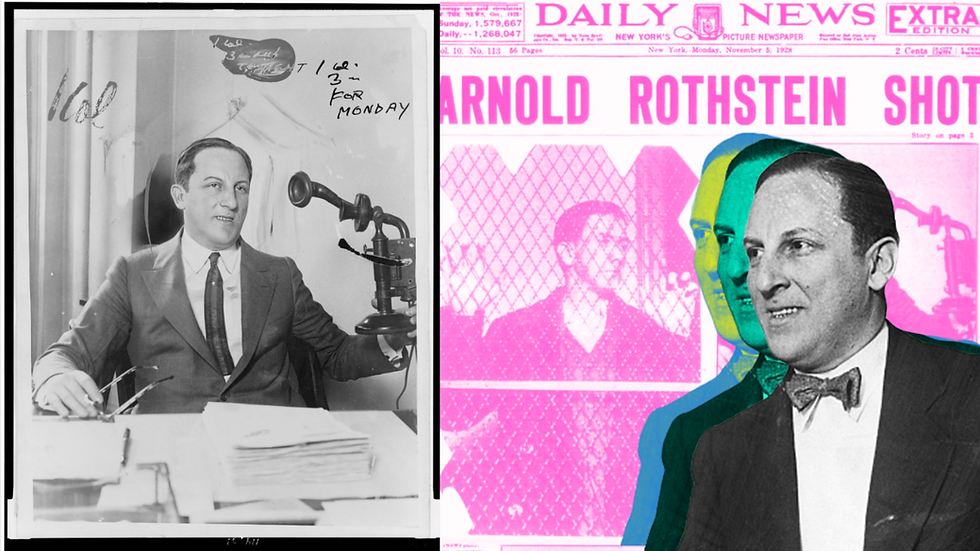

Arnold Rothstein—widely known as Mr. Big, The Brain, or The Man Uptown—was New York’s most notorious gambler and is credited as one of the architects of organised crime in the United States. Rothstein's life and eventual death in the late 1920s encapsulate a fascinating blend of ambition, wit, and a relentless drive for power that shaped an entire era of criminal enterprise.

On November 4, 1928, Rothstein was shot during a poker game at the Park Central Hotel in Manhattan, a dramatic moment marking the downfall of one of the city’s most infamous figures. Rothstein would die two days later in a hospital, taking with him secrets that might have shed light on countless criminal enterprises. His life story is a captivating account of early 20th-century New York, a time when gambling was an art, fortunes were won and lost over a card game, and the streets were ruled by underworld moguls like Rothstein.

A Prodigy of the Numbers Game

From an early age, Rothstein had a natural talent for mathematics and an almost uncanny ability with numbers. Growing up in a well-off Ashkenazi Jewish family in Manhattan, he was the son of Abraham Rothstein, a respected businessman known as "Abe the Just." Arnold, however, had little interest in following his father’s righteous path. Unlike his older brother, Harry, who pursued a religious path to become a rabbi, young Arnold was drawn to games of chance and the thrill of gambling. His father may have been a man of strong principles, but Arnold was a boy of boundless ambition. Reflecting later on his early passion, he once said:

“I always gambled. I can't remember when I didn’t. Maybe I gambled just to show my father he couldn’t tell me what to do, but I don’t think so. I think I gambled because I loved the excitement. When I gambled, nothing else mattered.”

By the time he was in his late teens, Rothstein had already amassed a small fortune from craps and poker, enough to open his own casino by the age of 20. A few years later, he had established himself as a fixture in New York’s high-stakes gambling world, known for his extraordinary winning streaks in card games. However, those wins often came with a price; rumours circulated that Rothstein had a habit of fixing games to ensure favourable outcomes.

The Black Sox Scandal: A Legendary Fix

Rothstein’s reputation as a manipulator of outcomes reached legendary status in 1919 with one of the most scandalous episodes in sports history: the “Black Sox Scandal.” Rothstein’s associate, Abe Attell, reportedly paid members of the Chicago White Sox to intentionally lose the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. It was one of the earliest examples of a large-scale sports fix, and Rothstein’s involvement, though never legally proven, became the subject of much speculation. When the scandal broke, Rothstein was called before a grand jury. He denied any involvement, asserting, “The whole thing started when Abe [Attell] and some other cheap gamblers decided to frame the Series and make a killing... But I was not in on it, would not have gone into it under any circumstances and did not bet a cent on the Series after I found out what was under way.”

Behind closed doors, though, Rothstein seemed to relish the outlaw image. While he might have distanced himself from the scandal publicly, he never denied his role in private circles. There were whispers that he had netted $350,000 from the scheme—a fortune by the standards of the time. In the words of historian Leo Katcher, “Rothstein won the Series, he won a small sum… it actually was about $350,000. It could have been much – very much – more. It wasn’t because Rothstein chickened out.”

Building an Empire of Vice

The 1920s, a decade of prohibition and excess, provided a fertile ground for Rothstein’s expanding empire. Beyond gambling, he began investing in nightclubs, racehorses, and brothels. These ventures cemented his place in New York’s underworld and earned him immense influence, both financially and politically. At one point, he was reportedly paid half a million dollars to mediate a gang war, underscoring his status as an essential player in the criminal landscape.

Rothstein’s wealth and power grew exponentially, with his fortune eventually estimated at $50 million. He was rumoured to carry as much as $200,000 in cash at all times—an astronomical sum for the era. With such financial prowess, Rothstein entered the realm of high-level loan sharking, reportedly padding the pockets of police officers, judges, and politicians to ensure that his operations ran smoothly. His reach was such that he wielded influence not only over the criminal underworld but also over the very institutions that were supposed to contain it.

The 1921 Travers Stakes Scandal

In 1921, Rothstein pulled off one of the most infamous horse-racing scams in American history at the Travers Stakes. Under the name "Redstone Stable," he owned a racehorse called Sporting Blood. Working with the influential trainer Sam Hildreth, Rothstein orchestrated a series of moves that saw Sporting Blood’s odds skyrocket before the race. Rothstein placed a large bet, and after Hildreth unexpectedly withdrew his own prized horse, Grey Lag, Sporting Blood went on to win. The result was a windfall of more than $500,000 in winnings for Rothstein. Though rumours of his involvement in fixing the race swirled, he avoided legal consequences once again.

Prohibition and the Rise of Organised Crime

With Prohibition, Rothstein found new opportunities in bootlegging and narcotics. He expanded his operations to smuggle liquor from Canada and overseas, establishing speakeasies and becoming the first to import high-end Scotch whisky in his own fleet of freighters. This move demonstrated his business acumen and marked him as one of the first to capitalise on the illicit liquor trade in a grand, organised fashion.

Rothstein’s influence continued to grow as he brought in notorious figures like Meyer Lansky, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, and Dutch Schultz under his criminal umbrella. By this point, he was so integral to the city’s underworld that even Tammany Hall, New York’s infamous political machine, saw him as a necessary ally. In this respect, Rothstein was not just a gambler; he was a kingmaker and a pioneer in the world of organised crime, bringing a businesslike approach to the chaos of the streets.

The Final Game

In the autumn of 1928, Rothstein’s luck began to falter. During a high-stakes poker game in September, he lost $320,000—a considerable sum even for him. Rather than paying, Rothstein claimed the game had been rigged and refused to settle his debt. This refusal created tension with George “Hump” McManus, a fellow gambler and one of Rothstein’s acquaintances. Two months later, on November 4, 1928, McManus invited Rothstein to a poker game at the Park Central Hotel. That night, Rothstein was shot.

While Rothstein lay dying, police questioned him about the shooter, but he upheld the underworld’s code of silence. According to one account, when asked who had shot him, Rothstein simply put a finger to his lips, choosing silence over cooperation. His enigmatic last words to the police were,

“You stick to your trade. I’ll stick to mine.”

McManus was arrested for the murder but was eventually acquitted due to insufficient evidence. There were many theories about Rothstein’s death, with one possibility pointing to the legendary gambler Titanic Thompson as the orchestrator of the poker game’s fixed outcome. Rothstein’s debts and refusal to pay left a trail of enemies, each with their own reasons for seeking vengeance.

The Legacy of Arnold Rothstein

Rothstein’s death sent shockwaves through New York. His meticulously constructed criminal empire quickly fragmented as his associates and rivals scrambled for control. Figures like Frank Erickson, Meyer Lansky, and Bugsy Siegel would rise from the rubble, but New York’s criminal landscape was forever changed. The fall of Tammany Hall’s hold over organised crime in New York is often attributed to Rothstein’s death, marking a shift from the old world of political gangsterism to a more fragmented criminal enterprise.

Ten years after his passing, Rothstein’s once-vast fortune had evaporated, declared insolvent by his brother, Harry. His death signalled not only the end of an era for New York’s underworld but also the dawning of a new, more complex phase in American organised crime. Rothstein may have died over an unsettled poker debt, but his legacy as a gambler, fixer, and mastermind continues to captivate those who study the early days of American crime